Independent Thinking — A Deeper Look at Herd Mentality

- George Yin

- Jun 1, 2024

- 5 min read

In our digital age with platforms facilitating the rapid spread of ideas and opinions¹, both credible and not, it has become easier than ever to align on a majority consesus². Social conformity is a fundamental aspect of human behavior³. As a result, its influence can be seen across various societal outcomes, including market dynamics⁴, political movements⁵, and public health responses⁶ with implications a tad broader than standing in line or Silly Bands.

While much research has focused on the group dynamics that facilitate conformity, less is known about the individual psychological characteristics that predispose some individuals to follow the crowd more readily than others.

Setting the Stage

We’ll first need to understand Cognitive Dissonance Theory before layering individual variability.

Imagine you’re with a group and suddenly asked a simple question. You’re all shown a line on a flashcard and asked to pick the matching line from three options on another card. Unbeknownst to you, everyone you’re with will all pick one wrong choice because (drumroll) they’re all paid actors!

While this sounds like the premise for a social experiment video, this was in fact Solomon Asch’s Conformity Experiment⁷. In each group tested, all but one of the participants were actors pretending to be real participants, and at certain times, these phonies would all choose the incorrect line.

The purpose was to determine whether the real participant would conform to the group’s wrong choice. Remarkably, Asch found that about one-third of participants conformed to the obviously incorrect majority at least once⁸. However, when at least one confederate gave the correct answer, the level of conformity by the real participant dramatically decreased⁹.

If we take a closer look at this experiment though, somewhere along the line the participant (the real one) needed to make an internal decision- between their choice and the group’s objectively incorrect judgment. This scenario embodies the essence of Leon Festinger’s Cognitive Dissonance Theory¹⁰.

Dissonance Emerges

Dissonance occurs when a person experiences a conflict among their beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors that challenges their self-concept or necessitates a change in one of the conflicting elements to reduce discomfort.

Reduction: To alleviate this discomfort, one has the choice of the following menu:

Change one or more of their conflicting attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors to make them consistent.

Acquire new information that outweighs the dissonant beliefs.

Reduce the importance of conflicting beliefs.

Applications and Examples:

Post-Decision Dissonance: Post-decision dissonance occurs after making a decision, especially when the decision is difficult and involves a significant choice between alternatives. After making the decision, people often experience dissonance because they may doubt whether they made the right choice. To reduce this dissonance, they may seek out information that supports their decision and devalue the alternatives they did not choose. (I didn’t really need to go to that meeting anyway!)

Effort Justification: Effort justification is a specific type of cognitive dissonance where people come to value an outcome more if they have put a lot of effort into achieving it. The rationale is that if they invested significant effort, time, or money into something, they need to justify that investment by perceiving the outcome as worthwhile. This can lead to an increase in the perceived value or attractiveness of the outcome. (I’m paying way too much for this apartment, but it’s okay because the location will make it worth it!)

Induced Compliance: When people are induced to engage in a behavior that is inconsistent with their beliefs, such as being forced to fish, they might change their beliefs about the situation to reduce dissonance — they develop an interest in fishing. (I love fishing!)

In the case of conformity, this Cognitive Dissonance Theory remains a cornerstone in enabling a majority opinion through its paths of reduction.

Let’s Make It More Complicated:

In the dissonance framework, discussion centers around why a person responds the way they do. The focus now turns to why processing dissonance is variable across individuals.

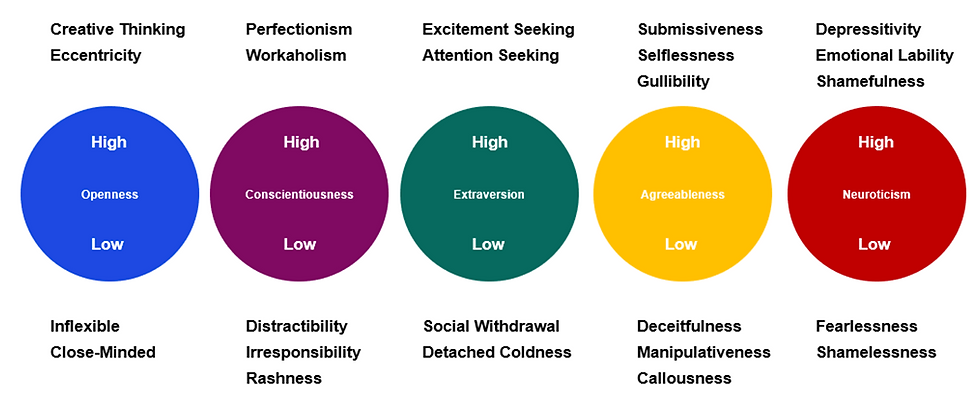

While there’s an ocean’s worth (this is a pun, you just don’t know it yet) of literature around social conformity and decision-making, these foundational ideas help serve as a substantial base layer for an additional framework — OCEAN. OCEAN refers to a psychological model that describes five broad dimensions of personality: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism¹¹.

There are no two people alike — personalities between people are never one-to-one. We can conclude then that the degree of influence and decision-making thereby varies as well. While there are overall trends that can be observed such as the Cognitive Dissonance Theory, the degree to which one is susceptible, for example, each reduction option is variable.

The Big 5 (OCEAN)

But on top of these traits are additional considerations:

Cognitive Abilities: How cognitive factors such as intelligence, critical thinking skills, and information processing styles impact herd mentality.

Emotional Regulation: Investigation into how individuals with different levels of emotional intelligence and regulation respond to social pressure.

Personal Stake: Personal interests regarding the context of internal decision-making such as prior knowledge

And now to stir the pot, all these aspects are intermingled! Each affects the other in a non-linear fashion. Your emotional regulation could impair your openness, or maybe your cognitive ability impairs you from certain dissonance reduction options.

A Scenario:

While understanding the granularity of groupthink among a population might lead us down a rabbit hole of exploitation (X many customers received a dopamine hit because of a sound during this advertisement), there is a brighter path.

Understanding the combinations of OCEAN traits can be likened to determining a person’s emotional DNA, and the applications of this understanding could (hopefully) catalyze and nurture a more resilient and thoughtful society. By identifying key traits and abilities that influence herd behavior, it is possible to develop targeted interventions that promote independent thinking and resilience against undue social influence.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, misinformation and varying opinions about vaccines spread rapidly on social media platforms. Group dynamics played a significant role in shaping public opinion and behaviors, with many individuals conforming to the predominant views within their online communities.

People’s reactions to vaccine information can be analyzed through the lens of the OCEAN model — individuals high in Openness may be more willing to explore diverse viewpoints, whereas those high in Agreeableness may conform more readily to maintain harmony in their social circles. Determining the makeup of traits in these individuals could help us better understand how they deal with cognitive dissonance and the reconciliation of conflicting information about vaccine safety and efficacy with their pre-existing beliefs.

By understanding these underlying psychological and personality factors, public health campaigns can be tailored to address specific traits and reduce conformity to misinformation.

Where most advertising campaigns tend to hinge on demographics, interests, and density to determine the effectiveness of their endeavors, it’s possible to benign exploration into the regional concentrations of certain OCEAN personality traits. In doing so community interventions can help address dissonance reduction more effectively, while messaging can focus on leveraging their understanding of the general population. For instance, individuals high in Conscientiousness might respond better to structured and detailed information while those high in Extraversion might be more influenced by messages delivered through engaging and interactive formats.

Ending Thought:

This multifaceted exploration not only promises to deepen our understanding of the psychological underpinnings of conformity but also holds the potential to empower individuals to navigate social pressures with greater autonomy. The answer isn’t as simple as determining the personality makeup of an individual but rather the potential applications of this discovery to circumvent psychological pitfalls that come from herd mentality.

Herd mentality and groupthink aren’t necessarily a bad thing. Some have a net benefit from conforming to the group — in situations where people have limited information or expertise, following the majority can lead to better outcomes, as the group’s collective knowledge outweighs that of any single person.

But by illuminating the characteristics that predispose individuals to follow the crowd, maybe we can foster a society that values critical thinking and celebrates the courage to stand apart.

Sources:

8,9. Asch, Solomon (1951). “Effects of group pressure on the modification and distortion of judgments”. Groups, Leadership and Men: Research in Human Relations. Carnegie Press. pp. 177–190. ISBN 978–0–608–11271–8.

I think what struck me, even when I had initially read this the first time, is the broader notion of social performance as well. I think that idea is embedded as well in everything you've written here but perhaps a different way of framing the 'roles' we believe we are playing. I too personally face a lot of personal tension (dissonance) with my constant conformity and performance, and yet it feels inevitable

Love this