From East to Everywhere: Alibaba’s Global Influence and Fast Fortune DTC Models

- George Yin

- Mar 25

- 6 min read

Aspiring English teacher and KFC Manager reject, Jack Ma discovered the internet while in Seattle in 1995. Only a few days after being threatened at gunpoint in Malibu, many years before founding one of the world’s largest ecommerce and retail companies, and two and a half decades before his public rehabilitation by the People’s Republic of China, Jack searched the word “beer” on the world wide web. To his surprise, a follow-up inquiry, “beer china” showed no results. In that moment, Jack envisioned Chinese commerce as an indomitable force on the world economic stage. This epiphany would birth an international behemoth on June 28, 1999, in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China. Its name would be Alibaba, and its reach would be inescapable.

Jack and his 18 constituents were smart while they raised Alibaba. They recognized the obvious dupes that could be made from their company’s name if they ever made it big, and since “Baba” meant Dad in Mandarin, Jack and friends registered Alimama as a company name as well. However, even shelved, the spirit of Alimama would persist. Symbolizing inexpensive imitations, her ethos inevitably spread under Alibaba's influence, fueling a new era of frantic drop shipping, an endless wave of shoddy goods, and the corruption of the American Dream.

Beginnings

The concept of drop shipping isn’t new, even if the TikTok algorithm convinces you otherwise. Drop shipping has existed since the 60s and 70s, mainly through the mail order system. Companies such as JCPenney and Sears pioneered this concept with mail-order catalogs and developed fulfillment warehouses to speed up shipping, similar to Amazon’s FBA warehouses. With the rise of the internet, these mail-order companies soon shifted into ecommerce stores (at least they tried to). The world was taken aback. Overtaken by the excitement and potential of online business, venture capital funds pumped internet startups to impossible valuations, leading to the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2001. But, in the ashes, the strong emerged. In the 2000s, Amazon, eBay, and Shopify revolutionized the way goods were bought and sold online, offering user-friendly interfaces and robust infrastructures for sellers and buyers alike. The world was good, and the people rejoiced.

That being said, there’s nothing inherently wrong with drop shipping. Much like knives and jokes—it's the intent behind them that defines their impact.

Consider the Following:

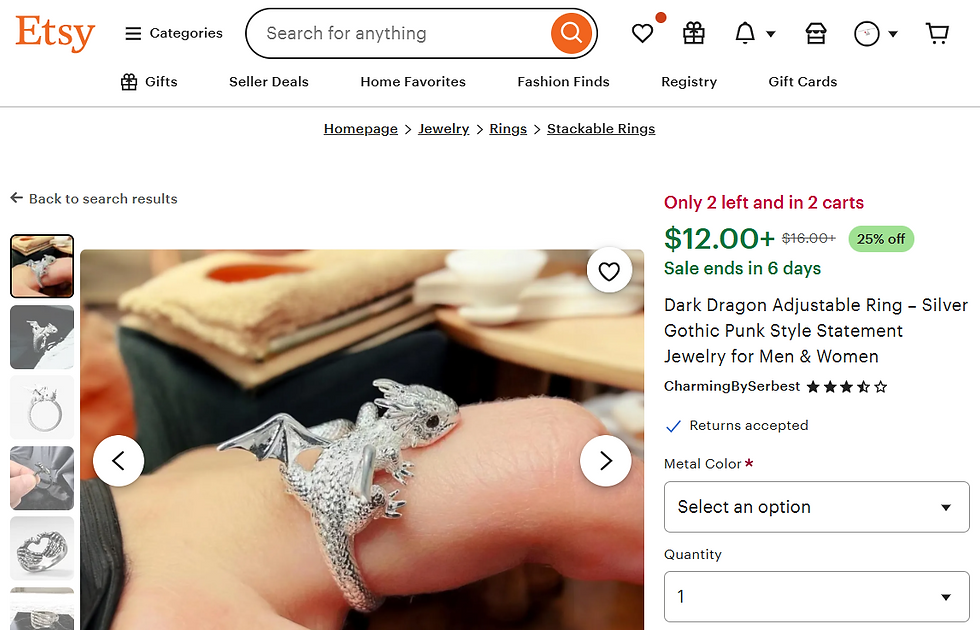

Etsy’s core value proposition stems from an authentic and human marketplace they’ve (arguably) worked hard to curate. Home to meticulously crafted handmade goods, the site follows the tradition of open craft fairs - sellers need only pay a small fee to list a product, and relinquish a small fee on each purchase. The consumer interacts directly with the supplier. This is a listing found on their website:

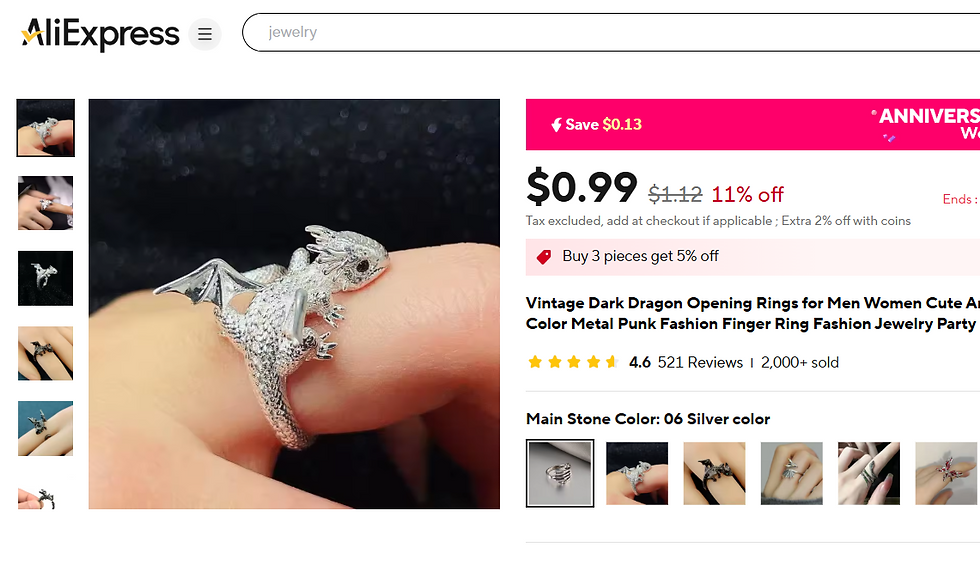

Alibaba’s platform is one where small and medium-sized Chinese companies can sell their products and services globally in a simplified model. Their e-commerce site, much like Etsy, is a bridge between supplier and buyer. These suppliers even sell on Alibaba’s offshoot, AliExpress, for more DTC operations if the aim is for individual goods rather than bulk quantities. Regardless, the goods on both sites are manufactured en masse. Customization for these orders often requires ~100 unit order minimums, and true quality is usually found when orders are big enough to personalize. This is a listing found on AliExpress's website:

Here's another one:

If you look hard enough, you’ll see these images are identical. And if you squint harder, you’ll see the frantic race of WFH business owners looking to make the fastest buck possible.

Alibaba’s core platforms—Alibaba, AliExpress, and 1688—have become the invisible backend of global e-commerce. For entrepreneurs in the West, these sites are a goldmine: access to thousands of manufacturers, ultra-low prices, and the promise of effortless scaling without ever touching inventory. Suddenly, anyone with a laptop and a PayPal account could be a "brand founder." This model of commerce—zero R&D, minimal oversight, and margin-first thinking—was seductive.

Alibaba made global supply chains accessible, and social media made virality scalable. With platforms like Shopify simplifying storefront creation and Meta ads offering laser-targeted reach, DTC transformed into a playground for arbitrage. Products from Alibaba, often white-labeled with generic logos and given trendy names, are sold at wildly inflated prices. The founders? Often anonymous, often short-lived. Their goal is simple: pump up ad spend, drive impulse buys, and exit before the complaints pile up.

The result was a market saturated with carbon-copy stores selling the same posture corrector, pet hair remover, or LED galaxy projector—all from the same source in Shenzhen.

There’s a hidden cost to this movement. A wave of ultra-low-barrier DTC entrepreneurship has led to:

Consumer Distrust: As scammy or disappointing purchases rise, trust in online brands falls. This hurts real businesses trying to build something lasting.

Environmental Toll: Cheap, disposable goods shipped halfway across the world for one-time use are fueling a silent environmental crisis.

Cultural Erosion of Entrepreneurship: The archetype of the founder has shifted from problem-solver to funnel optimizer. It’s less about mission, more about margins.

Evolution

As Alibaba continues to evolve and decentralize supply even further, the bar for starting a business will keep getting lower. But maybe that’s not the real question. Maybe the future isn’t about how easy it is to start, but how hard it is to matter. Although drop shipping isn’t new, maybe we’re viewing the end of a decades-long stage in the "Boom-to-Bust-to-Build" cycle as platforms evolve with the advent of new technologies like AI.

In the Boom phase, hype draws a flood of opportunists chasing fast money, often leading to oversaturation and low-quality offerings.

Common traits:

Overvaluation

Copycat behavior

Low-effort or speculative projects

Rapid user adoption (not always sustainable)

The Bust follows as consumer trust drops, regulation increases, and weak players fail. (Where I think we’re entering.)

Common traits:

Market crashes or downturns

Mass closures or bankruptcies

Loss of public trust

Platform crackdowns or stricter regulations

Then comes the Build phase, where sustainable businesses emerge, real value is created, and long-term innovation takes root.

Common traits:

Thoughtful innovation

Stronger products and infrastructure

Clearer business models

Trust regained through quality and transparency

This phenomenon shows up almost every time a new technology, platform, or market emerges.

Whenever there is a new platform or technology, separating hype from substance becomes the primary issue. An ideal example is the early App Store era, when developers flooded the market with cheap, buggy apps (remember iLighter or Sound Effect apps?) —many of which were clones or gimmicks designed to make fast money. This oversaturation leads to consumer fatigue and platform crackdowns. Over time, however, real value began to surface as creators who prioritized quality, usability, and long-term vision—like Instagram and Uber—rose above the noise.

Global sourcing, instant storefronts, AI-generated product descriptions, and plug-and-play advertising campaigns are becoming the default. As these tools commoditize the process of launching a product, being "fast to market" is no longer impressive—it’s expected. However, the same tools that fuel cheap hustle might also empower thoughtful innovation. The future lies not in how quickly you can start selling, but in how meaningfully you can build.

Founders willing to develop beyond the blueprint—to add true value, to prioritize sustainability, to create truly differentiated offerings—can leverage Alibaba’s scale without being consumed by it.

Think: small-batch creators using global sourcing to offer niche products. Think: ethical brands that transparently show their supply chains. Think: businesses that still believe a product should solve a real problem.

Ironically, the global nature of commerce is fostering a return to localism. Consumers are tired of generic, mass-produced products- they herald the beginning of the Bust stage. 71% of customers prefer local retailers even if it means a higher price. They’re craving stories rooted in place, culture, and personal craftsmanship (what Etsy should have been). Successful businesses of the future can leverage Alibaba-scale supply where appropriate—but integrate local, human, or artisanal touches to create unique value.

The products people buy are also becoming forms of expression—commentary on their values, aesthetic, humor, or worldview. In this sense, brands are no longer just vendors—they're curators of cultural identity. While consumer purchases have long reflected personal identity, it will become increasingly difficult to express individuality when mass-produced, dropshipped products all look the same. For some categories like dropshipped clothing, this can be detrimental. Especially when ~70% of Gen Z respondents now cite fashion as a primary means of expression.

I think the next evolution of global commerce won’t be about accessing more stuff faster. It’ll be about curating less, better. This doesn't mean that dropshipping will disappear, though. We’re moving towards strategic restraint—a return to slower, more thoughtful growth anchored in storytelling, values, and authenticity. The age of intention is coming, where building a meaningful business means crafting an ecosystem, both physical and emotional, not just flipping products. Alibaba may have democratized access, but what we do with that access—that’s the new frontier.

Comments